The Shoot Heard Round the World

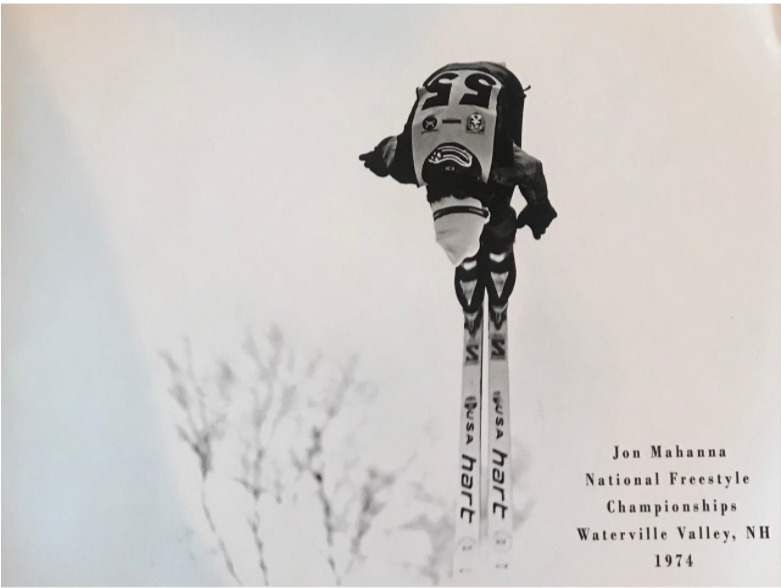

“Shoot (actually, a different word), I can do that,” said 19-year-old Jon Mahanna as he watched two instructors performing flips on skis at Killington, Vermont in 1967. The two were among the first ever to pull off the stunt. A week later Mahanna –now a longtime PSIA member, examiner and educator– tried it and the story and his picture quickly went around the world.

It was the beginning of what has come to be known as freestyle skiing, but in 1967 there were probably only a handful of skiers who could do a flip on skis. Jon Mahanna, a young instructor at Bousquet Mountain in Pittsfield, Mass., knew of only three. Stein Erickson was the first to popularize it, performing regularly at whatever American ski resort he was working at starting in the late 1950s. And there were Hermann Gollner and Tom LeRoy, the two instructors Mahanna saw in the air at Killington. Mahanna and his buddy and fellow Bousquet instructor, Jim Hollister, were at Killington to compete in a pro ski race.

The next week, Mahanna was back at Bousquet, where he and Hollister had been teaching since the 1963-64 season when they were 16 years old. With not so much as a practice somersault, on Sunday, March 12, 1967, Mahanna was ready to try what he had seen at Killington. Photographer Joel Librizzi from the local paper, The Berkshire Eagle, was at the resort to take the annual group picture of all the instructors. Mahanna told him he was going to try a flip and asked him to try to get a picture. Librizzi got the picture. It went out on the Associated Press wire service and was printed in hundreds of papers around the world, including the New York Times, where the photo ran next to a story about Jean– Claude Killy beating Jimmy Heuga in a race at Vail. Several years later, Hollister told the story behind the picture in an article for Ski America magazine. That article is reprinted below.

A few additional facts about Mahanna’s first flip: He wasn’t sure how it was going to end and he did not want to damage his own skis if it didn’t end well, so he borrowed a pair from the rental shop. The bindings may have been loose, possibly explaining why the skis flew off mid-flip. Mahanna was unaware he had lost his skis until he landed on his feet, skidded a bit and then slid on his face. A week after the picture was taken, he made his second attempt at a flip. The skis stayed on and he nailed the landing.

This was all early in Mahanna’s lifelong career in the ski industry. When the 1966-67 season ended, he joined the U.S. Air Force and served until 1971, including time in Vietnam. Upon his discharge, he returned to Bousquet as assistant ski school director for a season. Then came two seasons doing flips and more on the International Freestyle Skiers Association (IFSA) pro circuit, which included the World Freestyle Skiing Championships at Heavenly Valley in April 1974. On the pro circuit, he was sponsored by Hart Skis, Salomon Bindings and Nordica Boots and was on their Freestyle and Demonstration Teams.

Most of Mahanna’s career has been in ski school and resort management positions including stints as a ski school supervisor at Heavenly, ski school director, operations manager and general manager at Dodge Ridge, director of operations at Big Bear, director of operations and president/general manager at Angel Fire Resort in New Mexico and director of mountain operations at Bear Valley. He also worked as director of skiing at Eldora Resort in Colorado. In 2005 he was given the SAMMY Award by Ski Area Management Magazine for leadership in the mountain resort industry.

Mahanna has been an Alpine Level 3 certified member of PSIA-AASI since 1972. He is also Alpine Level 3 certified in the Canadian Ski Instructors Alliance (CSIA). He currently lives in Columbia, near Dodge Ridge, where he continues to train new instructors and teach seniors in the resort’s Masters Clinics. In addition, he is an examiner and educator for PSIA-AASI-W senior educational clinics and senior specialist accreditation exams. He wrote a snowsports workbook, “Alpine Guide to Certification,” for all levels of PSIA certification. In 2018 PSIA-AASI-W honored Mahanna with the Nic Fiore Award, which recognizes a member who has given much service to the division and the membership.

Shoot, what a career!

-C.P. McCarthy

The following article by Jim Hollister was published in Ski America Magazine in 1973.

LOOK MA

It did happen to be one of those amazingly crisp, winter sunshine days: crackling snow, cool air, fast skis, the effortless yet pulsating rhythm of the mountain was there.

As I recall that day seven years ago, it seems as though it was all set up. A happening that would transmit the seed of what has become the hottest dog in dogging–“the flip that flipped the world.”

In retrospect, the skiers present felt a wave that broke through every previous structure. The limits of ski technique had been expanded two-fold.

Jon Mahanna and I had known each other since early childhood. We were both born and brought up in Pittsfield, Mass., USA. Our parents were the closest of friends and we followed suit. We had gone through school together, and at 15 we had both been certified by the Canadian Alliance. By 19 we had been teaching at Bousquet’s, after school, nights, and weekends for five years. We lived for the snow and both knew that skiing was a way of life.

For Jon it was a release that he worked up to for at least a year. For most of the winter we had had a hard time keeping him from flying. He needed frequent reminders that he was obligated to more than a dozen ski classes for the remainder of the season. Our general feeling was, what would be left of Jon (if he did what he was talking about) we could buckle into one boot. So for him the restraint had been great.

‘Til then Stein was the only flip. Tom Leroy and Herman Gollner had tried a couple at Killington but Jon had ideas about soaring.

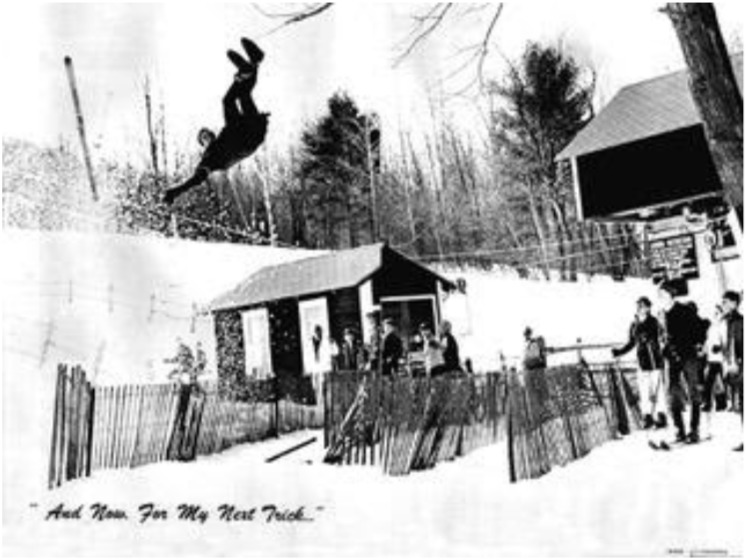

We discovered the bump in the early morning after a couple of warm-up runs before classes. At the bottom of the hill a mound had built where skiers had stopped for the chair. More or less that final christie location two feet in front of the lift line where you can’t be missed. We started doing tip drops off the mound over the lift line fences. That was a thrill. It was early enough so the Sunday morning throng had not set in. We became furious in returning for one more. The lip was perfect. We were getting up over 12 feet and going out between 30 and 40. The landing was absolutely flat but the balance we were able to maintain allowed us to land as softly as a glider. It was beautiful, but the psych-out was more than Jonathon could handle. By 10:00 he knew he had to do it.

Court McDermott, our ski school director, got behind the idea, and during lunch he announced over the P.A. that the “Berkshire’s first flip” was happening at 1:30. The bump was perfect, but Jon couldn’t be satisfied. He got out the shovel and began building snow. Soon he had doubled the height, and the lip began to look like a launching pad. He kept saying he needed to guarantee enough time to get all the way through the flip. By our estimation, if he got off at all, he’d have enough time to wax his skis and check his bindings long before getting to the peak.

The size of the bump was enough to draw 200 curious and by 1:15 the lodge had emptied out and close to a thousand stood exchanging gasps of bewilderment. They understood that what they were going to see had to wind up super, no matter what.

As time drew near for his jump, the electricity and intensity was so great, Jonathan asked that we go up alone. We stood on the hill some 300 yards above the bump. It was apparent in Jon’s face that fear had mastered all the adrenalin he could possibly use. We both shook, or more like trembled, as he readied to fly.

From where we were standing the question changed from whether he’d have enough time to get around, to whether he was going to end up in the trees. We finally got closer but still stood 250 yards above take-off. The murmur of the crowd seemed to ask: Is he going to start from way up there? For Jon it had to be. I took his poles and parka and as a last remembrance suggested he undo his safety straps. We talked about it for no more than two minutes and then he had to go. Halfway to take-off he was doing close to forty. The mouths of the onlookers dropped even before he got off. He approached the inrun at a tremendous speed that, combined with the lip sent him up and forward and out higher and farther than any of us had fathomed. What we didn’t know was that the force generated would cause both skis to release and come flying off one-third into the flip. The rotation was perfect and Jon came down square on his feet. His boots laid tracks 6 inches deep for 10 feet until he finally keeled forward onto his nose and skidded to a stop. The crowd panned and couldn’t believe it. The skis came down with a crash. Applause broke in spontaneous disbelief. Jon was surrounded by a sea of goggles and gloves.

Joel Librizzi, a local photographer with that particular talent for being in the right place at the right time, saw it too. He knew when his shutter closed that he had captured on film an instant to chronicle all skiing.

Within a week the story had spread. Jon’s picture had appeared in over 200 newspapers and in four languages from New York to Alaska to Paris and from Vietnam to Squaw Valley. Letters poured in from Florida and from Montreal. The change had come, and we knew then that what was hot was hot.

What’s best of all is that Jon is still doing it. The mule-kick, daffy, helicopter, as well as the double flip are part of his standard routine. He’ll be in the super exhibitions this year and as always the Berkshires will be rooting for the kid from Bousquet’s, who for one incredible instant took the whole country on an upside-down journey that many will remember for a long time.

By Jim Hollister